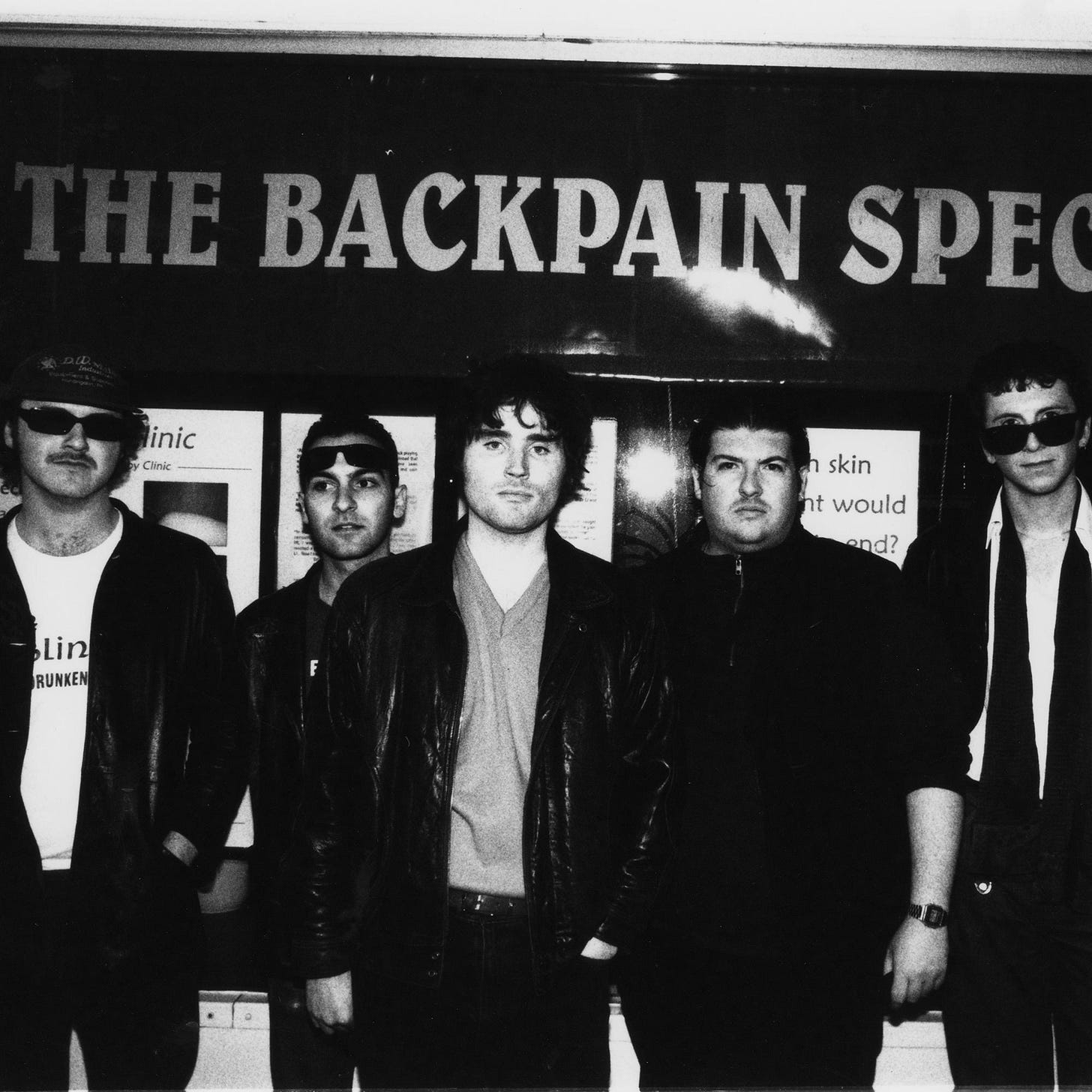

What's On Your Shelf? With Michael Cable of Vehicle

I spoke to Michael Cable, frontman of Vehicle, about books. Fresh out of the van from a four day tour with multiple (ironic) vehicle breakdowns, Michael expressed concerns that he wasn’t going to be wholly coherent for this interview. Half way through a long run of shifts, I could relate. As it turns out, I think our slight delirium lent itself to the conversation well.

We spoke about reading making him feel sick as a child, coming to literature on his own terms, and enjoying the exercise of language. We also spoke about his love of David Berman, Open Field Verse and his belief that hangovers are a necessary part of good art.

I listened to Vehicle’s debut album, Widespread Vehicle, on repeat whilst writing this. It feels like an album you could have been listening to all your life. I’ve found it playing over in my head since, both the music itself and the imagery it evokes. A gentle, humming piece of poetry that washes over you, pulling on familiar images; it feels a bit like dancing through a childhood dream, or watching an old memory play out from the window of a moving train. Talking to Michael about reading shone a light on precisely where the cinematic world of Widespread Vehicle came from.

Image by Dan Commons @dan.commons13

R: Does it feel like it makes sense for you to be interviewed about books?

M: Definitely. It’s what I spend most of my time doing really, reading.

R: People often think that they don’t read enough to have these conversations. But they always end up with plenty to say.

M: People feel like you’re meant to be this library full of stuff you’ve read, all ‘I read six books a week’. It’s not like that. If you’ve only ever read one book, you’ve probably got a lot to say about it. When you read a good book, it’s like you’ve been through something, it’s happened to you. Things that have happened in the book give you your own ideas, and help you see the world in a different way. You can even get that from one book. It’s definitely not about how many books you’ve read. I’ve got a good set of people who I talk about books with a lot. It can be a bit daunting, quite highly intellectualised. I’m lucky that I can talk to people about reading in any way I want to, or they want to.

R: Did you read much as a kid?

M: No. I couldn’t read a book without pictures in it, until I was about fifteen. Reading used to make me feel sick, when I was a kid. I’ve always been more into visual things. The first book I remember really enjoying was this book that my Mum got me and my brother, called Paradise Garden. It was this book about a little boy who…

R: [burps] excuse me. I’m going to be burping throughout this.

M: Sponsored by [picks up my drink] San Miguel.

R: [points to his can of ambiguous IPA] and whatever that is.

M: Yeah, about this little kid who runs away, and finds this kind of world. It’s in England. Each page has these amazing paintings on them, full of tangled webs, tiny little buildings in trees. There was this thing called Cafe Max, there’d always be a tiny little cafe in the corner. It might be a street, but then you could see underneath the street that there were houses. This Cafe Max, and tiny little people, really intricate things. At the end he finds this Paradise Garden through a brick wall in a street of terraced houses. That set me up for finding mundane places interesting, really, reading that book.

R: It sounds quite abstract.

M: I’m probably over-egging the pudding here a bit [laughing]. It’s big, it’s a bit like Ulysses. It was just a nice little book about a kid who finds a garden in a terraced street. But it’s quite surreal.There’s one page that I remember, with a load of houses, and you can see in the windows of them all. One house is filled with water, and you can see fish swimming in there. In another there’s someone having an argument, in another there’s a family, in another there’s bricks, or grassy fields inside the house. You know, none of it makes sense.

It’s interesting that Paradise Garden was the first text Michael mentioned. Listening to Vehicle, I found myself struck by the use of an image within an image - of one thing giving way to something else, of one idea being strung up within another. Michael speaks in metaphor and simile, and his songs do too. His description of Paradise Garden suggests all the magic and misery concealed just behind every day life, the height of the surrealist’s kitchen sink: magical worlds behind a terraced street. A particular lyric from Softspots stands out; ‘I can’t get them out of my head/like whole countries under the bed/ We’re all with someone else instead’ . This image of worlds within worlds, of one scene opening up into something else entirely, seems to sit perfectly with his description of Paradise Garden.

M: That was the first that I remember reading. In answer to your question, I didn’t really read properly until I was fourteen, fifteen. It’s a terrible thing, but I found all of that to be a bit out of my depth. I found it all a bit high-brow. I didn’t think I was clever enough to read. I couldn’t even read Harry Potter. I don’t think I had the attention span.

R: You said it made you feel sick.

M: Yeah, it made me feel queasy, without there being a picture.

R: It’s quite daunting I suppose, a bit of a sea of words.

M: I think that’s what it was, yeah. The impression I had of books, until I was a teenager, was that they just weren’t for me, basically.

R: It’s interesting that even when you’re so young, there’s this sense that this is either for you, or not. That’s how people often feel - that if you’re this age and you haven’t already read the classics, that you never can. Like it’s this exclusive thing.

M: You have to arrive at it on your own. It became a massive part of my life - because I’d found it without being force-fed it. It was a really good escapism thing. I read the books that I wanted to read rather than the ones I felt like I should be reading.

R: Do you remember what the turning point was at 15?

M: It was music, getting into the classic lyricists, Morrissey, you know, people like that. It was probably him really, finding out that his lyrics are coming from someone who reads a lot. I used to skive off school a lot. I found that I could get away with it if I stayed in Pudsey library. It started from reading NME as a teenager, I used to read about bands in there. I got into the Beats, that was the first one. The classic teenage boy thing, getting into guitar music, Jack Kerouac comes along, you know.

R: It’s an important trajectory.

M: I can’t remember which came first. I found Howl (Ginsberg, 1956) on YouTube. And then I did a fucking terrible thing. I wrote it out. I read that Jack Kerouac had written On The Road (1957) on a scroll, so I bought a scroll and tried to start doing that myself. It’s weird, as soon as I started reading, I wanted to write. It was kind of like I started reading more to get into writing.

R: Do you mean writing music, or?

M: Well, both really. Writing prose and poetry. At that age I didn’t know yet whether I wanted to be a musician or a writer or whatever, but it was something I really enjoyed doing, once I started. I can’t remember why or how I made that decision. Maybe it had to do with the music I was listening to.

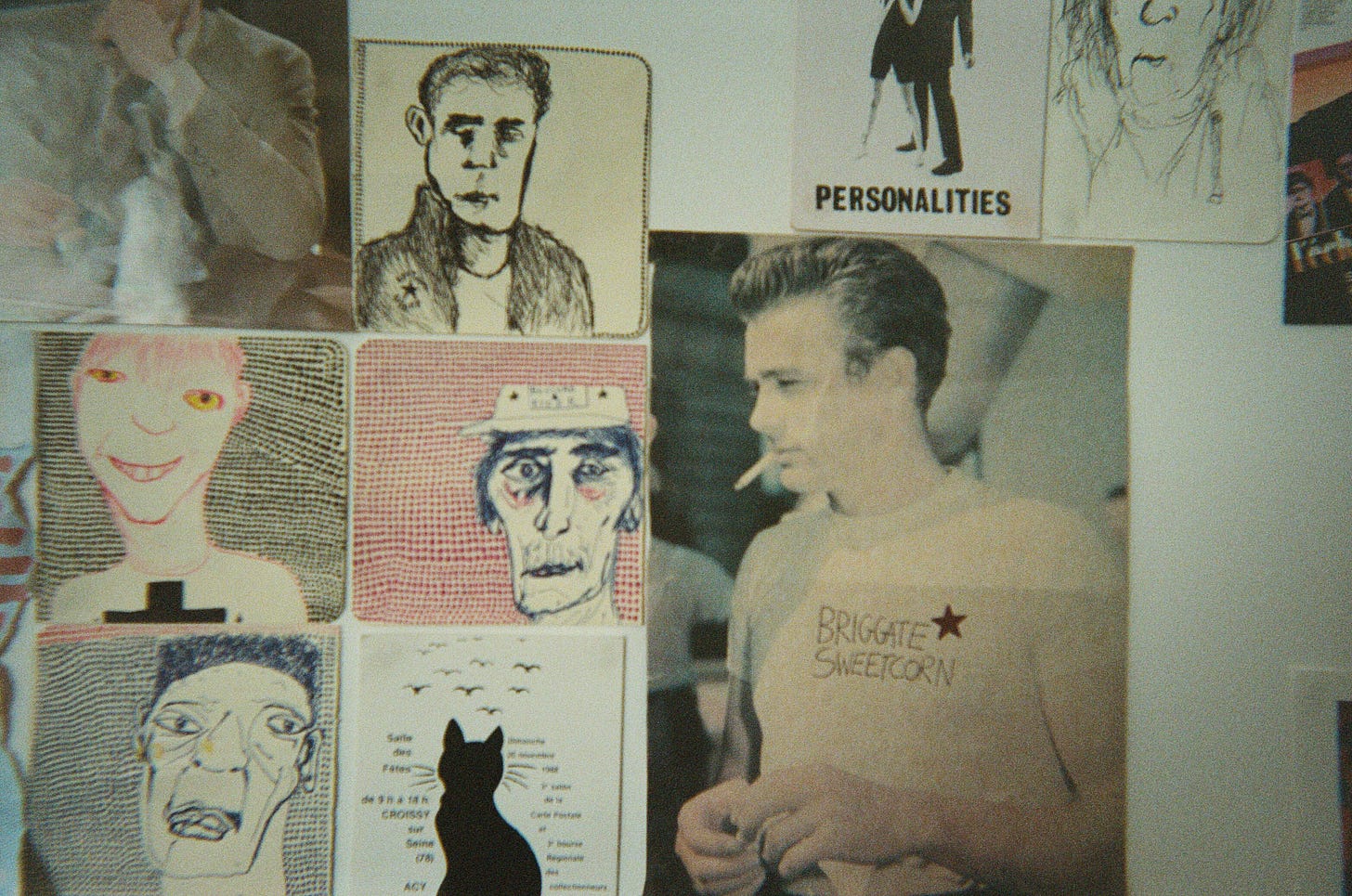

Image by Michael Cable

R: Do you remember how you got into that music?

M: That will have been through my Mum, definitely. She would always have good CDs on in the car. My Mum and Dad met playing in a band together, so they’ve always shown me good music. My Dad’s a bit of a rocker. He likes Sabbath and Led Zeppelin. He loves Beck, Super Furry Animals. My mum is more into cooler stuff, she showed me the Velvet Underground. They were massive for me. When I first heard them, I hadn’t heard anything that sounded so old but so exciting. It was before I understood anything about music or guitars, or the history of how music developed. Getting into those bits of literature probably had something to do with the Velvet Underground. Especially the Beats. I was always on Wikipedia as a kid, I probably found those things on there.

R: Just clicking through.

M: Going through the links, the chain. Morrissey would go on about Sylvia Plath. I remember buying Ariel (1965) when I was quite young and really getting into that. I got into all of them lot, that period of time, Philip Larkin, Ted Hughes. I went back and did all of the Symbolists, Rimbaud, Baudelaire. And then I kind of stayed there. I’ve always been shit at reading poetry.

This was clearly a lie because he goes on to enthuse about an awful lot of poetry.

R: I’m awful at reading poetry.

M: I don’t understand the canon of Keats and Lord Byron, whatever. I don’t get all that. Even William Blake, I struggle with. But I really like poetry where it’s modern language that you understand. When I read Baudelaire, it was written in a way where I could understand it, and was impressed by it as well. The way he plays with words, and sets these pictures in your mind. Real, visual stuff. That was stuff I really connected with. Maybe because I couldn’t read anything without pictures in it [laughing].

R: I just started reading Sartre, The Age of Reason (1945). I’ve never read any Sartre before. I had this idea that it would be this really challenging thing, and it’s just a woman talking about needing an abortion. It’s so incredibly normal, and relatable. The way the language pulls you in, even when it’s from 80 years ago. It’s always surprising to me.

M: Yeah, that’s what it’s all about, innit. I read Against Interpretation (Susan Sontag, 1966) recently. About how there’s a whole world of people who interpret things and write about it, and that stands in the way of every fucking piece of art that exists in the world. That’s why a lot of people are put off by it. Ulysses is a good example, where it is a bit nuts, but it’s not the book that people think it is, where it’s impossible to read. It’s just a story. Once you get going with it, it’s just a day. Someone’s day. You’re inside their head, and you’re inside Dublin, and not every page has to make sense. There’s a way of feeling the story, and getting excited about certain bits without having to have an essay at the ready about it. You know, Sartre, you think Oh fucking hell, this is gonna be a mountain to climb, but often it isn’t.

R: I think that comes from school as well. School can make people so excited about reading, but if it doesn’t hit in the right way, it can put you off completely. It only gives you one way of doing it.

M: I was shit at school, I failed all my GCSEs really. I didn’t go to uni or anything, so all of this is something I’ve arrived at outside of always understanding it, you know? It’s not something I understand academically, but I think that I prefer it that way. I don’t think I’d read as much if it was like that. When something is elevated in a certain way, it's out of reach. Which is why most people don’t read certain books - when they could, and they could have a great time reading it.

A lot of the books Michael cites as key influences, I think weren’t intended to be read as part of the literary canon or analysed in that way - they were meant to be felt, like he says.

R: So if you’re reading all of those things as a teenager - the Beats, and so on - were you then going into English at school and not feeling it?

M: [Ashamedly] oh, I just loved mucking about, I was just an idiot. I’m a bit in my own head a lot of the time. Even if I’m in a room full of people now, my mind will often wander. I couldn’t knuckle down really. I couldn’t sit well in the way the curriculum presents itself to you. I could only combat shyness by going and mucking about, and being attention seeking [laughing]. When I realised I could educate myself, with stuff that I enjoy, I stuck with it and found that I could express myself with these things that I was exposing myself to. You know?

R: Do you have any coming of age books that represent that middle-teenage bit?

M: All the stuff that I was reading then, I kind of don’t like anymore. I used to read a lot of William Burroughs. I feel like it just made me… [laughing] paranoid. I read a lot of books when I was a teenager that were very paranoid…shit blokes who were very cynical, had quite extreme world views. You know, The Fall (Camus,1956), Naked Lunch (Burroughs, 1959), Perfume (Patrick Süskind, 1985). I think that I was reading for the play of language. I wasn’t reading books because I liked the story. I was reading things because I liked the way that the words could dance along the page. I found that really exciting, really interesting, before I understood the whole weight of the story. Often I’d read something for that, and then only feel the story at the end. I think that was the coming of age thing really.

Image by Dan Commons

M: I used to read a lot of music autobiographies as well. I guess they’re quite ‘coming of age’. I love Viv Albertine’s one (Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys, 2014). That’s the best one I’ve ever read. Playing The Bass With Three Left Hands by Will Caruthers (2016). He was in Spacemen 3. That book is great. I lived in Rugby when I was a kid. All these places that they used to go into space via, I recognised from my childhood. Their music, it’s got a very gentle, deep sound to it, it’s very soulful. That, mixed with the knowledge that they were making all that music where I was a child, was a potent mixture. I guess that’s a coming of age thing. It made me appreciate the fact that I’ve moved around a lot, and it’s alright, you know?

R: Puts it all into perspective a bit. When did you leave home?

M: When I was… I guess I didn’t leave home until I was 20.

R: And that was to move here in lockdown?

M: Yeah, yeah, moved here. And I’ve just been here since really. I lived in Bradford for a bit, with my brother. I did live in Leeds when I was a kid. I went to school here. And then moved to York for college, because my step-dad had a job there.

R: And then you moved back to Leeds?

M: Yeah, they still live in York. I go over there now and again. I live near the Royal Armouries now. On the banks of the Aire. My flat’s on the other side of the dual carriageway. I basically live above the motorway. I actually love it, to be honest. It’s like that film Crash, but without being sexually attracted to cars and car crashes.

R: Which would be a perk, if you lived on the motorway, to be fair. The perfect place.

M: [laughing] Just looking over every night. Just waiting.

R: Did you read a lot in lockdown?

M: I did, yeah. That was a great period actually, creatively, for me. I realised a lot of things I wanted to do. I had a lot of epiphanies [laughing].

R: It was the time for it.

M: Just before lockdown, I’d really amped it up with the reading. At certain points in life, every now and then I stop and think: my brain’s different to how it was last year. It can be quite a nice thing, where you’re like, yeah, I think in a different way than I used to, and I’m quite happy with that. Each year your brain kind of changes shape, and it requires different things to enjoy, and different things to kind of oil it and maintain it.

R: You can feel the change happening.

M: Exactly, yeah. Just before lockdown, that was one of those periods where it was throwing out its old clothes, and getting new jackets and stuff. I remember reading Dubliners (James Joyce, 1914) just before the lockdown happened. That set me off on short stories. I got into Raymond Carver, in a big way. He’s probably my favourite prose writer, really. He’s the best. I think my favourite bits of writing are short stories. As a songwriter I can use that way more, that slice of things, way better than a novel. If I read too many novels, I kind of forget how to write songs. I start getting a bit too big for my boots and thinking I want to write a book.

I’ve since read Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981), and I can hear Carver in Michael’s lyrics. On Pam & Eric, the line ‘He comes home stinking of lies’ sums this up for me; a snippet of a life within a fragment of something else. A brief glimpse into a room, or a relationship, opens up into a chasm of feeling, of undisclosed feeling barely visible but pressing under the surface.

M: I read the Mersey Poets at that time, Roger McGough, Brian Patten, he’s fucking brilliant. The Mersey Sound, I think it’s called. They were a bunch of Liverpool poets in the sixties who took what the Beats were doing, but made it very English, very mundane. Talking about everyday things, which is something that I’ve always been interested in. Kitchen sink stuff.

The play Look Back In Anger by John Osborne (1956), that’s one of my favourites. It’s great. He’s horrible, this nasty fucking bloke, really. Those sort of characters interest me because there’s a way of writing about things like that, the language that is used… I just connect with it more. I certainly did then. Like I was saying, I think now I read things more for the story, and for how I live my own life. But I used to like reading things where the character would be going through a bit of shit. The way they would write that would be more interesting.

R: There’s a relief in reading about awful people doing awful things, and it still being relatable. I think that with Kerouac, and also Camus, especially reading them as a non-man, you read it and think this is fucking despicable, and that’s the joy of it. Of reading someone that’s just relentlessly despicable.

M: It’s darkly funny as well. I’m able to just look at the words and be impressed by this exercise of language. Henry Miller is like that as well. I really love his writing, but the stuff he’s writing about is disgusting a lot of the time. His whole view, and the way he’s living his life can be horrific. But his books combine that with complex characters, they’re not just horrible, you know, they’re human beings. That was his whole thing, writing the whole thing, not leaving anything out. Which is something that I got quite interested in early on. I wanted to read stuff about everything, really. Now I just like really good stories. At the moment I do, anyway. I guess it changes all the time.

R: You said you’ve got a lot of mates who read a lot.

M: I do, yeah. I’ve got a nice little network of people. Which is good because… it’s getting smaller as I get older, but I’ve always had a bit of a chip on my shoulder, really. I’ve always been interested in art and literature, and growing up I felt like it was a bit of a thing I had to keep secret, or didn’t always have mates I could share that with. Now I’m an adult, it’s the closest thing to academia that I could have, really. Having a system that enriches it all, you know? People you can talk about it with. When you combine that with having a good set of people who like having a laugh and having three day benders, but are also interested in art and music. That combination is a very good one.

This shrinking of the chip on the shoulder feels significant. Vehicle’s debut sees Michael cultivating more vulnerability within his lyrics. His previous band, Yorkshire cult classics Perspex, had a boisterous presence that has dissipated somewhat with Vehicle. Though the boyishness is undeniable, there’s something gentler, more composed. It’s the same poetry, perhaps in a more tempered form.

M: If you’re not hungover enough, I do believe that you won’t experience things in a certain way. I think hangovers create good art. Maybe with music, I don’t know about writing novels. Maybe that’s a different kettle of fish. But music, definitely, is full of hangovers.

R: It comes from discomfort, maybe?

M: Yeah, definitely. Or - well, it’s not even a discomfort, it’s the thing of…that glazed thing where everything’s a bit romantic, everything’s a bit… [raising hands in awe]

R: What are your most lent out books?

M: The most lent out… actually, every time someone wants to borrow it I just give them it and buy it again. Actual Air (1999) by David Berman. Jesus Christ, it’s fucking amazing.

R: OK, tell me about Actual Air.

M: Where do I start with that one? He can tell you how it is, not muck around, and make you see the world in a completely different way. You put it down and you can see different colours. It’s like doing a drug with that. It makes you appreciate every little speck of dust in the room. The way that his mind wanders in each poem and story. You get the feeling that he’s lived a thousand years in every room he’s ever been in.

A running theme seems to be things that make you see the world in a different way; poets, writers, hangovers. This interest in viewing the everyday through different lenses, trying on different perspectives, is conveyed throughout the album. We’re brought along on that journey, trying on different lenses through which to see the world around us. On S Windows we hear Michael sing of how ‘the pylons kiss the stars/ silver kisses for the stars/ one day I’ll get drunk and remember/ how the pylons kissed the stars’. The romanticised hangover haze described earlier permeates the album.

M: My favourite one, I think it’s called Cantos for James Mitchener. There’s a bit in that about his neighbour who’s like a relic from the 80s, he says he has a voice like a toy keyboard. His genre of person, these naff Patrick Bateman types, but maybe a bit older than him. The first wave of cocaine business men, but the older branch, not the younger yuppie branch. He’s saying that they all disappeared at a certain point. He says ‘the mironauts came for them through the mirrored ceilings’. I love this idea of the mironauts, this bunch of people who exist in mirrors, on the other side, looking through. It’s very surreal, but relatable. And it’s funny. Humour is a massive thing.

R: That’s the thing about David Berman’s lyrics. It’s so everyday, and commonplace, and then so abstract at the same time. And so funny, and so heartbreaking.

M: That’s it, that’s how you hit the money on the head isn’t it, with good art. You have to make someone laugh so that you can then make them cry. One without the other isn’t human enough. It’s cheesy then. Again, there’s a pattern here where I read things that I think can perhaps make me look at the world in a certain way. Like I said, I got into reading so that I could get into writing. The writers I get into…it’s like forming a line of, a board of executives in your own brain, who are all helping to give you the tools to have your own voice. Reading Actual Air, it helped me look at my own world, and figure out how to write about it in a way that I felt like only I could speak about, you know? I feel like he spoke my language.

Image by Michael Cable

M: Apparently Berman was influenced by the New American Poetry 1945-1960 anthology. Charles Olson came up with this type of poetry called Open Field Verse. Where you - I’m gonna butcher this - it’s basically letting everything in whilst you’re writing a poem. You sit down with the pen on the page, it’s almost like you’re not writing it, it’s just coming into your brain, you’re including all of this stuff. That’s how I’ve taken it anyway. When you write a poem, there can be anything in it. In the same way that you might be having a conversation and something might come into your brain. Or life can be like that. You’re doing one thing for a while, and then something else happens. It keeps it alive.

Listening to the album, you can hear the intentional openness of its subject matter, one image bleeding into the next. Michael’s scene-setting conjures a feeling that seems separate to the story of the lyrics themselves. He spoke earlier about reading more for the play of language than the story, of the feeling of the story hitting him after the fact. In some ways that’s true of the album too. Its poetry washes over you, creating a sense of memory and familiarity that’s hard to pinpoint. Like recalling someone else’s childhood memory as your own, or being in someone else’s dream perhaps. His abrupt weaving of different images and landscapes, informed by that open field verse approach, enhances this dream-like effect.

M: Actual Air, it let me know where I sit, with poetry especially. I’ve gotten into a lot of similar poets since. James Tate is brilliant, very lyrical, funny, surreal. This might be a David Berman thing, I’m gonna paraphrase, but ‘Kentucky is a room with feathers in the corner’, or something. I love images like that. That’s so loaded, you know? You could say that…Leeds is a urinal with a field in the middle of it… I don’t know where I’m going with that one, to be honest. I’ve had four days in a van with people farting and spilling beer.

R: My next question was going to be writers that have impacted your writing, but you just answered that pretty well.

M: I’ve been reading Frank Stanford recently, who’s another one I found through David Berman. I’ve fallen in love with his writing. It’s so…again, just playful. The way that you can say something that’s almost a joke, but it really makes you think. I guess what we’re realising is I’m more into poetry than novels, really.

R: Maybe that’s just where your brain is at for now.

M: I love reading poetry just before bed, because you dream in that way. It can shape the way you dream. And when you’re tired, you can feel it a lot more. You’re not thinking about the day you’ve had, or anything. You’re just in-between those two states. Each line can kind of flow off the page and spill into your brain.

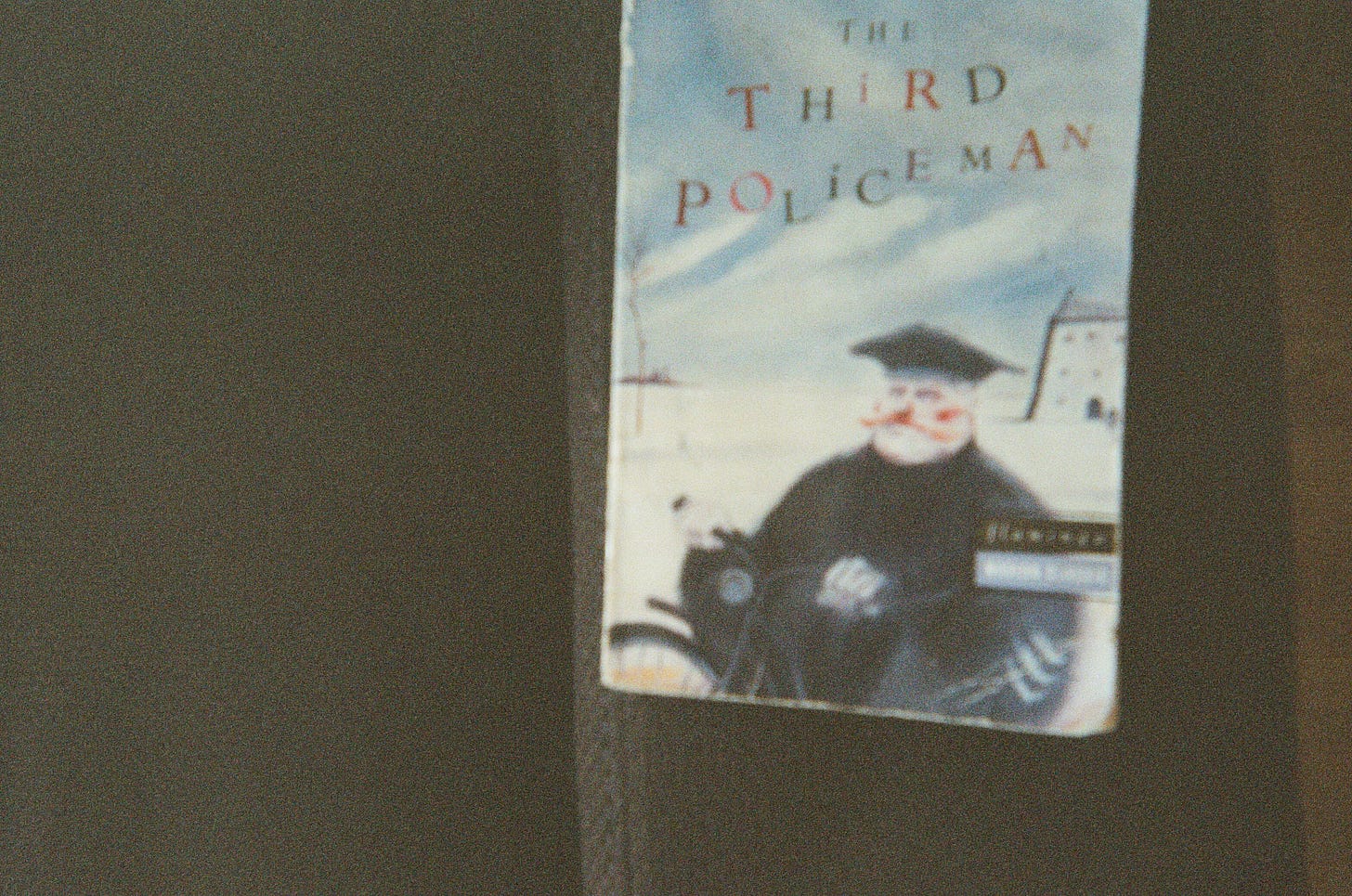

R: It sort of washes over you. I think we’ve covered everything. Oh wait, favourite book? Horrible question.

M: My favourite book ever is The Third Policeman (1967) by Flann O’Brien. Hands down, without a doubt. It’s just the best. You don’t really find out who the protagonist is or much about them. Their family dies and this bloke comes to look after them, a bloke called John Divney, quite a strange bloke. He comes in and raises this person, and they’re tricked into performing a crime. They murder a guy. After this murder happens, everything is different. Everything’s gone strange. It’s set in this dream-like version of Ireland where the roads never end. These policemen turn up. The whole thing is that…[pauses and shakes his head, laughing] Holes in this, isn’t there? Everywhere.

Image by Michael Cable

The guy goes and plants a bomb in this house, except it’s not a bomb, it’s like a suitcase. He finds the suitcase and it is a bomb, and it explodes. He goes to this police station and all the police officers are mental There’s this guy who believes that the bikes in the area are not what they are, you know? They’re not bikes, he believes the more time you spend with a bike, the more it becomes like you. There’ll be bikes coming into the house at night to stand by the fire. It’s like, if you spend too much time with your bike, you become 60% human, 40% bike. It’s full of mad stuff like that, it’s very surreal.

R: It sounds mental.

M: I just love the humour. Throughout the book there’s footnotes, because the protagonist is writing a biography of this fictional author called De Selby. It’s full of footnotes about these other writers who are also writing about De Selby. Each writer is at war with each other. One of the critics has gone AWOL and gone shady.This is all in the footnotes while the story is going on.

R: How big is this book?

M: It’s actually quite thin [laughing]. It’s only a couple of days. I don’t want to spoil it. That’s why I’m stumbling so much. A lot happens in it that you’re not meant to know. That’s why I’m explaining it like an idiot.

R: I’ll get a list from this interview, and hopefully read at least some of them. My list is so long. I like buying books more than I can keep up with the pace of reading them.

M: I’m the same, yeah. It’s ridiculous. I have piles of them in my room. Covered in dust.

Vehicle’s debut album Widespread Vehicle is out on Friday 20th June on Esco Romanesco. That evening they’ll be playing an album launch show at Mabgate Bleach - tickets are £5 OTD, and you should go.