What’s On Your Shelf? With George Orton of Gladboy

I spoke to George Orton about his bookshelf. A man of many bands, George is a member of Gladboy, Bug Teeth and Volk Soup. For me, this conversation cemented one thing clearly: George’s reading habits are as eclectic as the bands he plays in.

We spoke about his experience studying English Lit at uni, the Bad Sex in Fiction award and his fractious relationship with lyric writing. We discussed his interest in horrible books and the literary connections between The Fall and Pulp Horror. We also speculated on whether Isaac Wood (of original BCNR lineup) has read White Noise by Don DeLillo.

This was the first time George and I met – we arranged this interview over Instagram. Writing this up has been great, because George is now a good friend of mine. It’s a lovely thing to have your first conversation with someone on record, and to know that you’re about to become really good friends. I have huge respect for him as a musician and as a reader.

I think we were both a bit nervous prior to the interview. It took the first greeting at my front door to clock that we have the same accent. It turns out we grew up 20 minutes away from each other. That immediately diffused the nervousness.

G: When we spoke about this interview, you said to think about books you keep coming back to and want to talk about. I looked at my shelf and was like OK, I’ve got about three in mind.

As he speaks, George is pulling volume after volume out of a backpack and laying them out on my living room floor.

G: And then I was like…and that, and maybe that, and I guess what I’m reading at the moment, and…I’ve just got so much with me. Most of these are favourites, or at least things that I find interesting.

R: This one’s massive.

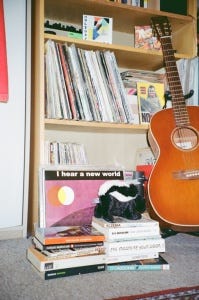

G: Yeah, that’s a collection (The Moons At Your Door: An Anthology of Hallucinatory Tales, ed. David Tibet, 2016). I haven’t read the whole collection, but it really reminded me of something that you and Ben spoke about. I’ll put these into piles.

He’s organising all of the books now.

R: [laughing] Have you got themes here?

G: Kind of. I don’t know why I brought so much. I thought it would be kind of funny. [Picking up a book: Eczema: Complete Guide to All the Remedies – Alternative and Orthodox by Christine Orton] This is written by my nan.

R: No way!

G: Yeah, she used to write about eczema. I found that quite inspiring. She used to be a journalist. I never got to meet her. My Dad had really bad eczema as a kid so she wrote books about coping with eczema as a child. She used to be a journalist. It’s very inspiring.

George starts taking his shoes off whilst he’s talking.

G: I found some of her books in my uni library.

R: You don’t have to take your shoes off, by the way.

G: I don’t know why I am really. I think I wanted some air. I walked here too quickly.

G: I just love horrible books. I’ve gravitated towards them more as my life has got more and more ordinary. The more I work 9-5, the more I want to read something completely unhinged. There’s an escapism to that. I don’t idealise the people I’m reading about. But I think pretty much every book I’ve brought, apart from that one by my Grandma, and this one which is a history book, they’re nearly all about very…

R: Dark things?

G: Yeah! [laughing]. Oh, and this one is about running actually (What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, Haruki Marukami 2007).

R: Have you always been drawn to horrible books? Or can you think of a time when that shifted?

G: My main exposure to literature was from my brother. He worked in a betting shop when he lived at home. Him and this woman he worked with would challenge each other to read the longest books possible. So he re-read The Count of Monte Cristo by Dumas (1844), which was like 1000 pages, with this woman at work. They were always reading Hemingway, trying to one-up each other. It seemed quite funny at the time.

As a result, he always had these books around the house. So most of the first literature I read belonged to him. Things like Camus and Kafka and American Psycho, A Clockwork Orange. Even things by Timothy Leary, about taking LSD. I was only doing my GCSEs but these were the books I was reading outside of school. So it might have stemmed from those being my main exposure to literature that wasn’t aimed at young adults.

R: I guess that sets the bar quite high in terms of adrenaline levels that you’re going to get from a book.

G: Yeah. I was very lucky to have someone around that actively read and left books around the house for me to pick out. And they weren’t all horrible, but those were the ones that definitely had a long-lasting effect. And in general, they broadened my horizons massively. It was definitely his influence that led me down this path.

R: Is he a lot older than you?

G: Yeah, he’s 33.

R: And how old are you?

G: 23. Yeah, he’s very intelligent. Reading all of these books whilst working in William Hill is probably how Ernest Hemingway would want to be read in Austerity Britain.

I don’t like macabre for the sake of macabre. There is a boundary. I don’t particularly like violent films. It’s not something I seek out. Maybe it’s because when you’ve got a narrator, you get so into their psyche. Maybe I just find it interesting being inside the heads of people who are in a different moral sphere to my own.

R: In all of my interviews, it’s sci-fi and darker books that tend to come up a lot. It’s made me realise that the dark books that I’ve read have stood out to me over time. Even though I usually opt for comfort over intensity.

G: I don’t know. I mean, reading is like life’s great comfort.

I thought that what you said about Sci-Fi in your interview with Ben [Fuzz Lightyear] was really interesting – about how you felt like most of the post-punk bands you speak to were inspired by Sci-Fi. I don’t know if you’ve listened to much of The Fall, but they’re almost meme levels of post-punk. Shouty man music.

R: It’s just what everyone else is now trying to emulate.

G: It’s interesting, lyrically The Fall are built on pulp horror. Writers like M.R. James and Arthur Mackey, who are both in that collection.

R: This one here? [grabbing The Moons At Your Door: An Anthology of Hallucinatory Tales]

G: Yeah. It’s very early, basically ghost stories. Whereas now I feel like speech-like singing inspired by The Fall is just used to make observations about how mundane our reality is, the foundations of it are actually in horror.

There’s this book called The Weird and The Eerie by Mark Fisher (2016) where he analyses the lyrics of The Fall. He talks about how the original definition of the word ‘grotesque’ was about animal creatures and nature, and he uses that to analyse The Fall album Grotesque, which has all this stuff about people turning into creatures, this mythical quality to it. It really made me think about the relationship between a musical genre and a literary genre.

R: There are so many connections to be drawn. Ben mentioned a lot of psychedelic artists and how they read Sci-Fi and fantasy.

G: I like the idea with Sci-Fi that you’re using other worlds to understand your own. I think that’s really cool. It’s not a genre that I know loads about, but it’s a genre that I’m fascinated by. I love Kurt Vonnegut. He uses the medium of science fiction to talk about something completely different entirely, to imprint his own bizarre worldview.

R: What did you do at uni?

G: English literature.

R: That makes sense.

G: I like books.

R: It’s all adding up. What did you do your dissertation on?

G: I did it on this book [picking up Cain’s Book by Alexander Trocchi, 1960]. It did kind of nail it in as a book I became obsessed with. Like completely neurotic about. I was spending lockdown with my girlfriend and I’d wake up at 2am like ‘I’VE HAD AN IDEA’. It must have been unbearable to be around.

R: So was the dissertation mainly about this book?

G: It was about diaries in literature. This book is a diary of a heroin addict. It’s semi-autobiographical. The author was a heroin addict that only published two good books. I compared that with Bridget Jones’ Diary (Helen Fielding, 1996), and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea (1938).

R: That sounds incredible.

G: It was utterly mental, and very entertaining, comparing such different texts. I just got so deep into it that by the end I couldn’t even think about diaries. It was about why you would use a diary as a format for a novel. I think ultimately it’s used in quite a lazy way. People have a diary as a format because it means the narrator is just addressing themselves.

That George was drawn to pulling connections from such diverse texts makes a lot of sense to me; when you listen to his music this tendency is apparent. Contrasting sounds and themes are pulled together in a really poetic way, sometimes jarring, always compelling. I’m thinking about Gladboy in particular here.

Watching Gladboy live, I was blown away by their resistance to stick to any one genre or sound, and indeed also their resistance to members sticking to one role. The band veers perhaps between psych-rock and art pop, but so many other elements make brief appearances that it’s hard to pick any one way to describe it.

All five members really share the space, with each sound stepping forward to take metaphorical centre-stage at different times. George and Sonny (Mitchell) switch playing drums and guitar during the set, and vocalist/percussionist Janani Arudselvanathan’s vocals flit between backing and lead from song to song. There is no simple consistency, more of a constant flow that lends itself to their genre-elusive sound. Anyway, back to George talking about diaries.

G: You know when you read a book, and you think ‘Why is the narrator telling me all these things?’ And then you find out at the end that they’re having a conversation or they’re another character. If you write a diary you kind of cut out that ambiguity. It was…it was very interesting. Very all-consuming.

R: It sounds it. Cain’s Book was prosecuted in the obscenity trials in the sixties. I studied the obscenity trials at uni, so I always find it interesting when I come across a book that was censored.

G: There was a Scottish poet called Hugh MacDiarmid, a very popular poet, who came out and called Alexander Trocchi ‘cosmopolitan scum’ because Trocchi was in the counter-culture in the sixties. He basically just spent all of his time having sex and taking hard drugs. There are some incredible passages in that book. It’s not a perfect book, by any means, but when it’s good, the writing is just unbelievable.

R: And it’s semi-autobiographical?

G: Yeah – it’s basically him, just with a different name. That and his other novel Young Adam (1954) are basically about his life. I’m very envious of people that can write about themselves. I find it really difficult.

R: Had you read it before uni, or did you read it whilst looking for something to write your diss about?

G: I read it before. I heard him described by Irvine Welsh as the George Best of literature.

R: That is an incredible description.

G: Yeah, I thought it was really cool.

R: How long have Gladboy been going?

G: Since 2018. It was actually through shared reading and music. It was a bit like what you said growing up in Essex – going to school and not really knowing many people with the same interests. I went to university and met Sonny, our drummer. It sounds so pretentious but the first time I saw him, he had his hair dyed white and was wearing this suit with a copy of fucking Metamorphoses in his back pocket. I was 18, and I’d come from such a conservative nothing-y town like Braintree. And seeing that was just like ‘Oh my god, people I’m interested in exist’.

I have also recorded an interview with Sonny which will be birthed onto Small Distractions Club eventually. I go through phases with writing, so this project comes in sudden bursts.

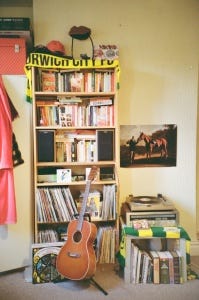

R: It does stand out to you. I did the same at uni, I definitely walked around with books in my hands. You’re signalling to other people.

G: Exactly, I mean, if you didn’t think people cared about what you’re reading then no one would have bookshelves with every book they’ve ever read. We met and we started playing music to entertain ourselves, then we started getting booked, so we expanded. We became a 6 piece. We supported quite a lot of quite big artists in Norwich, and headlined Norwich Arts Centre, which was the coolest venue you could get. But then lockdown hit and at that point we’d been together for three years. Our bassist lived in Leeds and we hit such an impasse that I really struggled to get around. Not playing gigs meant I was reading and writing a lot more, but I feel like I kind of lost two years.

G: As much as lockdown had a lot of downsides, I got back into reading completely. I had so many books staring at me from my shelf that I hadn’t read. Over lockdown I started ploughing through them. It was For The Good Times by David Keenan (2019) that really got me back into enjoying reading.

R: That is a beautiful book.

G: It’s the cover that brought it into my life. I had been reading stuff before that that I hadn’t enjoyed that much. And then picking that book up, I just remembered what it felt like to love reading.

It’s very experimental, in how it’s written, but also very plot-driven, and I think it’s rare to find a novel that can balance both of those aspects – of having a page-turning quality but also having such a unique voice and style.

R: It’s easy for one to overshadow the other.

G: Yeah, because you go to different books for different things. Sometimes you want to feel the language, with a book that’s more prosaic, and other times you want a good story, like one to get to the end of, and that for me just balanced both. It’s about the Troubles in Northern Ireland, set in Belfast. It’s got it all, man. I read it in a couple of days.

R: I love it when you get a book like that.

G: It had been so long since I’d enjoyed reading a novel.

R: And when you get that feeling where you could just sit there for hours, and then you do… it’s the best feeling ever.

G: It’s such an important book to me.

G: Towards the end of lockdown, when things started returning to normal, a few of us decided we were going to move to Leeds, where there are more bands interested in doing a similar thing to us. And where we knew people would hear us for the first time, because as much as Norwich was really good for us, it’s so insular.

R: Leeds is a good place to be.

G: It’s kind of like the next chapter. Unintentional pun.

R: You do grow out of the place you went to uni. As much as you love it, you need to leave at some point. I miss Sheffield so much but I couldn’t have stayed any longer. It’s always going to represent that time.

G: Moving really influenced my writing. Most of my writing became about new experiences, migration and moving. I found myself really enjoying road novels and stuff. Which sounds so dramatic considering I just moved out of my uni city. I think it’s subconsciously where I’m at, with still trying to process being in a new place. This is the ultimate road novel [handing me As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner, 1990].

R: I’ve never read any Faulkner.

G: He’s pretty intense. That’s a road novel in the least conventional sense. A mother has died and her final wish is for her to be buried somewhere quite far away. So her family walk her coffin there. Each chapter is told from a different family member’s perspective. As the journey goes on you find out how flawed their relationship is.

As the book goes on the body is starting to really smell because she’s been in there for weeks and they’re walking in the heat. One of them has broken his leg and it’s just so… my brother is like ‘This is shit because it’s too accessible’. And I’m like mate if you think this is accessible you’re actually broken.

This was one of the first books I read after moving to Leeds. When I moved into my house I had a couple of months where I just could not get a job, and it was a bit bleak.

R: Do you feel like the move to the north affected your lyric writing?

G: Definitely, yeah. Our stuff on Spotify up until recently wasn’t really what we’re about anymore. Living with the people I play with, we’ve had a lot more time to record, and to think about music. We’ve been recording every day which is so good.

But I have such a fractious relationship with lyric writing. I’m so critical of it. Particularly with other bands, even bands I like. And so as a result I find it so hard to get anything down on the page that I feel happy with. I’m so envious of writers that are really disciplined. I just try to say too much at once. Music is such an abstract form that we connect with. I want my writing to be more than that, I want it to have something to say, and sometimes I don’t and I need to just accept that.

R: It’s hard, especially when you have a clear idea of what you want to sound like. I’d imagine a lot of what you’re writing is actually really good, but if it doesn’t fit in with what you’re wanting at that moment, then it feels like it’s not working.

G: I get so much envy of writers when I feel like they’ve accomplished exactly what they’ve set out to do. I mostly write character-led compositions from other points of view. Recently I’ve wanted to write in a more honest way. But I find that quite difficult.

R: You could just pretend that it’s a character, but it’s actually you.

G: I’m sure they all are in some ways.

R: Just develop a full stage persona.

R: I normally ask about how your relationship with reading has changed over time. For most people, when they leave school and start work or go to uni, they stop reading. But you studied books. Did you stop reading for pleasure in that time or was it all still interconnected?

G: I’m honestly quite ashamed of how I spent my time at uni.

R: I am too! I feel terrible that I didn’t use it to study more.

G: Yeah, genuinely. Now I’m working and I realise that my full-time vocation was to get paid by the government to read, I’m just like WHY didn’t I care more? I just spent an entire year, second year of uni, smoking weed and playing Xbox. Going out. I was playing gigs and stuff and I did have a good time and make a lot of friends. But I’d had this honeymoon period with literature right before going to university, of reading all of my brother’s books. And then I got there and started having all these completely new experiences.

It got to the final year of my course and I did this incredible module about Nonsense Literature – things like Alice in Wonderland and James Joyce. It shifted all my perceptions of language. It completely rewired the way I thought about writing and reading.

Hearing George describe the impact of this module on Nonsense Literature was, for me, inextricably connected to Karloff, their 2022 release. Elsewhere George has described the song as his twisted re-imagination of what life was like before the indoor smoking ban; ‘a totally unrealistic view of that world…it’s a track propelled by its own naivety’. The lyrics evoke a sense of unreal cartoon-like movement, shifting from one place to another in a nonsensical yet thematically driven way. You can sense the impact of that module bleeding through into his lyricism.

R: Tell me about your most recent release, Karloff.

G: It was a demo. We recorded it in our basement a few months ago. It just happened that we were recording Bug Teeth and also recording ourselves at the same time. To me, it felt like both songs ended up feeding into each other. They’re both, for me, music for nighttime. Not in a relaxing way. They’re both kind of dark. They’re so different but I find them so similar.

R: I guess you’re going to see all those little connections.

G: Yeah, I see connections that most people probably won’t. We recorded it in our basement. We had spent so long on singles that we started recording ages ago, and were hyper-obsessing over the most minute details. We just thought fuck it, shall we release something that we’ve just recorded?. If you spend too long toiling over something it will never get finished. We were like this sounds good, let’s just get it out.

R: Especially if that feels more like what you sound like now, rather than trying to make older things fit.

G: It just felt natural, really. Because it was a demo, it felt like a more authentic recording. We probably could have recorded something better. Our band has 6 members and that one only has three of us on it, so the next thing we record will hopefully be able to represent what we’re all about, rather than just what a few of us are about.

R: You must get so much variety from that. Karloff already has so much range in it. It’s really cool. Are there any other modules you did at uni that particularly stand out as being game changers?

G: I had a teacher whose taste in books completely aligned with mine. Robert Lowell was an American poet that he introduced me to. This book [Life Studies, 1959] has a poem that became my favourite poem. It’s called Skunk Hour. There’s a group of people having sex in their cars. You get a description of that, and then the perceptive shifts to a skunk mother leading her pups and eating from an empty tub of sour cream. It sounds like such a bizarre image, but something about it really moved me.

R: I’d love to do an analysis of different ways of writing sex scenes in books. There are a few that I’ve read recently that have really stood out to me as being less about describing the sex itself and more about where people’s heads go. People zoning out, but that relating to what’s happening in an abstract way.

G: Even just in that book I can pick out a couple of really weird ones. Have you seen the bad sex award in fiction?

R: No?

G: It’s an award for really terrible sex scenes in books. Morrissey wrote a novel, and it won the bad sex award. There’s this line from it that – I feel like it’s followed me throughout my life.

R: I’ve never read any of Morrissey’s books.

G: I mean after this you definitely won’t want to. [reading from online] ‘The award is to draw attention to poorly written, perfunctory or redundant passages of sexual description in modern fiction’. Morrissey’s reference to ‘a giggling snowball of full-figured copulation and bulbous salutation’.

R: Ewwww.

G: It’s really weird, isn’t it?

R: He went so downhill.

G: ‘Breasts barrel-rolled across Ezra’s howling mouth’. Yeah, sorry. Not a very nice thing to read to someone I’ve just met.

R: But it is interesting. There are so many different ways of doing it, and the ones that have stood out to me, or the ones that make the most sense to me, are the most abstract. The ones that try to describe things in detail just don’t work, which is really interesting.

G: My girlfriend is a writer doing the prose MA at UEA which is a really prestigious writing course. They’ve just written a story where someone has sex with a moth. And another one where someone has sex with a computer. I’m just starting to realise that all of them seem to have some weird sex in them. I like how inventive it is, and it is completely like nothing I’ve ever read before.

George’s partner is PJ Johnson, published writer, frontperson of Bug Teeth and a prolific reader. I have also recorded an interview with PJ about their reading habits, which will arrive here at some undetermined point in the future.

R: We don’t have much time. Tell me about more of these books. What’s this? [picking up Territory of Light by Yūko Tsushima]. I love a tiny book. Partly just because I am a pussy, and if I have a massive book I get stressed about how long it’s going to take me to finish it.

G: Well, this book is an interesting contradiction then. Excluding the book of poems and the play that I’m reading at the moment, it’s the shortest book there, by some considerable range. But it took me quite a long time to finish. It’s only 94 pages, but it’s so heartbreakingly sad. I really struggled reading it. I only read it in a few sittings, but I was really spacing them out.

It was a bit of a fever dream, so I can’t quite remember the details. But there’s a narrator living in an apartment, in a city. It has the most beautiful lighting in this huge open room, but the light is so bright that it’s almost blinding her and she can’t see anything. It works as a kind of parallel to all these horrible things happening in her life. She keeps attracting all these awful events. The book is by the daughter of one of the most famous Japanese novelists, who I think was gay and committed suicide. That darkness really informs her writing.

R: It sounds really interesting. I really like a short book that is a really intense look at one feeling. Like a sort of microcosm.

G: Exactly. It’s kind of like a collection of short stories because each chapter is about a different day in her life. They’re all linked. They could probably be read in isolation and you would still understand what’s going on.

When someone asks me to recommend a book, I usually recommend either For the Good Times (David Keenan) or White Noise (Don DeLillo, 1985).

White Noise is about a professor of Hitler studies at a university. It’s about his life, and it’s very weird and strange. There’s an air-borne toxic event. No one knows why the air-borne toxic event has happened. It’s kind of like a pandemic, but it doesn’t really do that much. Afterwards, everyone is very shaken up by it, so they decide to practice for if an air-borne toxic event happens again. And then they end up having a practice for a practice.

It’s basically all about simulation, simulacrum, and it’s ridiculous. It’s so mental, but so funny. There’s one bit where he gets obsessed with wearing thick-mirrored sunglasses, and he’s wearing them in bed, next to his wife. He’s describing her, and how he can see that she’s looking at her reflection in his thick-mirrored sunglasses. I just found it so funny.

R: That sounds like a Black Country, New Road song.

G: I actually wondered if those lyrics were inspired by that. I think the guy from BCNR is into quite a lot of post-modern fiction. It’s so similar to that. If it isn’t then that’s a really weird coincidence.

R: What about Look Back in Anger, what’s that?

G: That’s a play I’m reading at the moment. John Osborne was part of the Angry Young Men, which is a group of men, white angry, working-class men. It’s a kind of essential working-class one-room play that was paraphrased for an Oasis track [laughing]. I’m not very far into it. I sometimes find reading plays really difficult. Do you find it difficult to imagine plays when you read them? Or do you find it quite easy?

R; I think I probably find it really easy to imagine the specifics of the action, and what’s happening step by step, but less so the atmosphere, which makes sense because it’s not described in the same way as in a book. I like Arthur Miller.

G: I quite like Tennessee Williams, he’s that kind of era of American literature.

R: A Streetcar Named Desire?

G: Yeah, there’s such a…one of the great, hyper-masculine characters. His plays, I went through a little phase when back home recently. When I’m at home I find myself reading so much, because I mean…Essex. There’s nothing to do other than see my mum, which is great, but I spend the rest of the time reading in my room. I probably read like four Tennessee Williams plays when I was back – as you do, just relaxing. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Glass Menagerie, Streetcar – really good. Really grave, really great. What more could you want?

George and I recorded this interview last year. When editing this piece, I checked in to find out what the latest is with Gladboy. He said the following:

G: We’re about to begin a new and exciting adventure. I’ve been writing on the bus before and after work most days, with a view to having a completely revamped set. We’re hoping to really hit the ground running after the summer.

Gladboy are playing at Oporto in Leeds on Thursday 6th June, supporting Duvet alongside Mother Said. I had the pleasure of seeing them play last year, and it was a real treat. Pure, immersive psych-rock fun. You’d be mad to miss it.